Sam Peckinpah Era Un Hombre For Sure

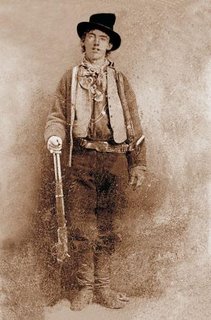

Billy The Kid, friend of the vato and terror of tyrants

1. reversed da guerro type -- cuter in person!

2. favorite remark: "Come and get some"

I've seen you standing there stunned in the spotlight

I've seen the sweat streak the pain on your face

Cause you're caught like a clown in a circle of strangers

Who do you screw to get out of this place?

"One For the Money" (Kris Kristofferson)

There's a key scene in Scorcese's Gangs of New York (2002) when, along with protagonist Amsterdam, we encounter a life-size statue of Chief Tamanend, arm outstretched in vintage "halt" position, looming in the corridor leading to Boss Tweed's office.

There are still some great films being made, despite the pathetic mercantilism and bloated egos of the Hollywood studio systems and personnel. When such films occasionally emerge, they're rarely understood and appreciated, either critically or publically. An offbeat, literate, period piece like, say, Mary McGuckian's The Bridge Of San Luis Rey (2004) is as far over the heads of American audiences as the Peruvian rope bridge itself.

[OK, the metaphor sucked, but you gets it eh?]

Great films, like Gangs, impart timeless, "spiritual" information beneath their topical/mundane levels -- not a big sell in our Kar Krash Kulture. Studio types smothered and butchered Peckinpah's Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid for decades because they wanted more "action" (you know, bang bang bang and falling stuntment) in the film. They tried to do the same to Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West. Not coincidentally, both films document the squeezing-out of Large Men from an (over)civilized Western World.

Very topical.

In the apocalyptic context of Gangs, ole Chief Tamanend -- one of those rarest of beings, a truly great man -- haunts Boss Tweed's hallway for good reason. Tweed's corrupt, Masonic "political machine" has adopted the Chief as mascot . . . without his permission or sense of personal honor. Scorcese's inferring something crucial about mid-nineteenth century political and spiritual corruption (Tammany Hall) of course -- but he's also telling modern Americans something vital about our own decrepit ideo-political structures and collective spiritual State.

Especially on America's enervated East Coast, semi-secret "fraternal orders" still call America's tune. The very air of the Eastern Seaboard is thick with corruption; gravity feels trebled there, and many of the citizens are in a constant state of zombified dis-spiritment. For this and similar reasons, Yr 'Umble Servant Little Dynamo rarely ventures east of the Rockies. Everything east of them mountains goes downhill right quik . . . to the Very Pit, indeed.

The coup of Skull-and-Bones (Kerry, Bush, et al.) is well documented, of course, but endless current examples likewise obtain. E.g.: Her Foulness, Katherine Harris, is supported by underground Masonic and ultra-right groups, including the Freepers (who, not coincidentally, also back punks like (Psycho) Phil Paleologos of New Bedford's infamous Shawmut Diner for positions on little-known powerpoints like Massachusetts' Governors Council.)

European/American Masonry mirrors its double-eagled emblem. It's your prototypical Necessary Evil. The U.S. couldn't have been founded, built, or maintained without various fraternal/secret societies. Particularly in the post-WWII years, loose fraternities were the backbone (yes, some snakes have them!) of American culture. In Little Dynamo's hometown of Vallejo, Kaliforknee, such organizations staffed the churches, constructed the improvements, fathered the families, kept the Order. Many members were solid men -- men of generosity and goodwill, loving their country and fearing God, doing their best in a dangerous and fundamentally nasty world. So it was across much of America.

But as with Boss Tweed and Tammany, the hierarchichal structure and occult power-lure of secret societies opens them to praetorian (the religious would say "Satanic") influences. In Gangs, Tweed's bargain isn't principally with the New York/American people, but with the Devil ("Butcher Bill") himself. Thus Scorcese suggests that, in our nation's last days, Chief Tamanend -- whose name was appropriated and whose principles were befouled -- must raise his sculpted palm outward against them, like the guardians at the Argonath, the massive statues of ancient heroes flanking Anduin's entrance to Minas Tirith in Tolkien's Lord of the Rings, warning away the Witch-King of the North: Here evil shall halt. You are warned.

Sergio Leone's brilliant, innovative Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), like Sam Peckinpah's Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973)-- and like Scorcese's Gangs is an eschatological elegy encompassing more than a particular time and geography. Leone's main baddies are railroad tycoon Morton, iconic of European/neo-American Masonic occultism -- specifically, necromancy -- and Frank (the Devil, chillingly played against character by Henry Fonda.)

Indeed, Leone's underground storyline culminates in a high-noon faceoff between Frank and taciturn protagonist Harmonica (Charles Bronson) at the denoument of the Western World. A very old and persistent evil must be eradicated before the 20th Century West (in reality, the post-historical New Heaven and Earth) can emerge. As in Gangs, the Masonic "craftspeople" appear to serve "progress" and civilization: but their bargain with the Devil runs too deep, and they -- and their civilizations -- become hopelessly lured and ensnared.

Whereas Peckinpah's Pat Garrett is compressed and naturalistic, Leone's Once Upon a Time is elliptic, stylized, and temporally elongated, each gesture stretched to maximum, with dialogue minimal (Leone used only 15 pages of dialogue script for a three-plus-hour film.) Most of Leone's "conversation" occurs in the landscape of the desert, and of his characters' faces.

In all three films, the question is: Who will inherit the Land? That's why Leone's Harmonica is oft seen carrying or whittling on a vampiric stake. Frank/Satan, in the crucial transtemporal scene at Mesa Verde, gloats to faux-aristocrat, robber-baron Morton that the West is about to have a "new owner" (himself!!)

In both Once Upon a Time and Gangs, the influence of the Irish and Catholicism in America/the West is revealed as central to overcoming Satanic influences and organizations: McBain's Station in Once Upon a Time provides not merely physical water to drive the railroad engines, but, via Jill (the "Waterbearer") the feminine "spiritual water" the frontiersmen so desperately need. Like former prostitute Jill, it's water reclaimed from pollution by evil, and Whore Babylon is offered an opportunity to return to Origin-Virgin as the positive and nurturing aspect of the Great Mother.

Like Pat Garrett, Once Upon a Time is considered elegiac of the "Wild West" -- a closing off of the ancient Heroic Age by increasingly "civilized" and hyperlegalized "civilization." Harmonica refers to this in his enigmatic ellipse to Frank concerning "an ancient race." As with the barbed wire fences of the scheming ranchers in Pat Garrett, no place remains for Great Men (i.e., for masculinity.) Instead, America heads down the wide blacktop toward Homeland Security, Total Information Awareness, and the Prison Industrial Complex.

The heroic/classical Great Life of men, ritualized and bounded by codes of honor, is foreign to matriarchal civilizations fronted by small or mediocre men. Leone's Harmonica, Frank and Cheyenne are morally diverse, yet each is Promethian. This is best illustrated in the meticulously ritualized final Shootout Scene between Frank and Harmonica. Malevolent as he is, Frank adheres to primordial male precepts, not attempting a "cheap shot" at Harmonica (and thereby salvaging a sliver of redemption.) Likewise, at many points in the narrative Harmonica could dispatch Frank, but instead literally "saves him" so other, necessary scenarios can play out, and their duel can eventually resolve in ritualized fashion -- similar to the arranged, theatrical, culminating faceoff between Amsterdam and Butcher Bill in Scorcese's Gangs.

Thus, as the Titanic strides of Harmonica delineate the terrain for the forthcoming civitas of Sweetwater township, Leone isn't merely foreshadowing 20th Century America/Western society. Harmonica -- already anticipating his showdown with the Beast -- is demarcating an eschatologic terrain, the Biblical New Earth of Revelation. As with Pat Garrett's Billy or Apocalypse Now's Captain Willard, good-guy Harmonica is paradoxically a killer, a primal force of destruction, semi-deific Hammerman.

Like Odysseus, even the "good guys" of the "ancient race" have, as Cheyenne (Jason Robards) cannily notes, ". . . something to do with death." Modern civilization, with its hyper-protections, endless codifications, and carefully rationalized cruelties, cannot -- must not -- grasp the practical superiority and wholeness of such men. But without such beings, civilization and new ages cannot be secured: evil runs amok and swallows any emergent resurrective order. Nor are such men vigilantes -- they're the opposite of the moralistic blood-mob that blabbers, in self-destruction, for Barabbas. To guys like Harmonica, dealing death is never gratuitous, fiscally determined, or otherwise Small. The self-imposed codes of such men -- their spiritual dimension -- keep their Inner Animal in check.

Don't confuse that with a perfect world. When Pat Garrett's deputy, duly warned to walk forward peaceably, instead turns to betray Billy, the Kid shoots him in the back. In a later scene another deputy, agreeing to ten paces yet wheeling to fire at eight, is shot down by the Kid, who turned with gun poised, waiting patiently as the count began, already knowing that treachery was inevitable. Honor appears cheated and undone, but isn't. The ritual code, though harsh, is intact: had the first deputy come forward, he'd have been tied, gagged, and preserved. Had the second lawman held his bargain, he'd have gotten a fair shootout (and died anyway!)

Accidents are strictly for amateurs.

In the Special Features DVD addenda to Once Upon a Time, the commentators consider the Mesa Verde scene a mistake by Leone -- partly because it seems to drop into the film from nowhere. But there are no mistakes in this meticulous, spiritually astute classic.

The film pivots upon the scene. Leone breaks the narrative's linearity and inserts this very brief scene into the dramatic, blood-red cave/cliff backdrop of Mesa Verde precisely to highlight the atemporality or transtemporality of the action and characters. It's a Dreamtime sequence populated by meta-human characters practicing ancient ritual techniques that function outside time.

In a wide, middle distance shot, we see Satanic Frank, robber-baron Morton, and various aboriginals going about some undefined -- but clearly purposeful -- business at a major Mesa Verdean site. In the foreground, an aboriginal woman tends a smoky cooking fire, from which Frank, hidden behind a shelf, rises into view with a long, double-pronged fork in his hand, upon which is spitted a piece of roasted flesh.

As crows caw in the background, Morton says to Frank: "I've had enough of your butcher tactics." [emphasis added] Frank reponds by popping the piece of speared meat into his maw.

Only in recent years has Western science begun to investigate -- and to take seriously -- the prospect that sorcery, including ritual human sacrifice and cannibalism -- were fundamental practices at various Southwestern "Anasazi" sites, including Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde. (Despite various theories, and mostly due to paucity of broad-spectrum evidence, neither anthropology nor archaeology really have much idea who the "Anasazi" really were, nor their predecessors, the "Archaics." Sufficient archeo-astronomic study has been done at Chaco to ascertain that the site Complexes were intimately connected, astronomically aligned, and very carefully and intentionally "decommissioned." In many instances, Chaco Complex structures were literally deconstructed stone-by stone. See, e.g., the Solstice Project's findings.)

The more knowledgeable (and sane) Native American medicine people of today do not share the politically correct/New Agey naivete of goofy Baby Boomers for all things aboriginal. They understand that evil dwells amongst all peoples of the earth, and most of them won't go near sites like Chaco and Mesa Verde. Bad medicine, they say . . . very bad.

Yo. The land is alive, after its own fashion. It retains and resonates the energies of its inhabitants.

Terror is particularly resonant. Sorcerers, whether archaic or modern, know this.

Amongst most pre-modern Mesoamerican cultures, public propaganda claimed that "propitiation of deities" necessitated fertility blood-rites. Underlying, however, are primal motivations of dominance and control by self-styled "elites" via techniques of mass-terror.

Same as it ever was. Spectacle is effective. See Joey Goebbels.

Blood-spectacle is particularly effective, imprinting deeply on both the individual and sub-collective (cultural/tribal) consciousness.

Somehow, pre-1968, Leone got hooked-in to the sorcery/cannibalism activities of certain Southwestern aboriginal peoples and their sites. Morton's "butchery" line isn't coincidental, and Frank then proceeds to, literally, show the money-man who's really the land's New Boss, kicking the cripple's crutch out from under him -- while in the camera's background, occupying only a frame or two, an aboriginal man sits cross-legged and impassive.

Leone then pans-out to a wide shot of the bustling Mesa Verdean site, and Frank refers to the land's "new ownership."

Meet the New Boss, same as the Old Boss.

In the film's flashback-conclusion, just prior to The Shootout, a youthful Frank emerges from a great rift in Monument Valley, striding into gradual focus like humanity's painfully slow collective awarness of the Enemy rising from the Wasteland's depths. The close-up of demonic glee in Henry Fonda's face is one of the most startling, discomfiting moments in film. I didn't think Hank had it in him -- and I'll bet he didn't either!

:O)

Leone then reveals, indirectly, the Native ancestry of Harmonica. First we see a classical Roman arch, plopped with anomalous -- and psychopathically sinister -- genius amidst the desert. A few neo-Centurions, members of Frank's gang, lounge about and upon the craftwork. The structure suggests the Crucifixion, of course, and also the brickwork of Masonry. The necromantic theme appears elsewhere in the film, usually associated with railroad-magnate Morton -- his European/Atlantic origins, his "striding dwarf" memento-piece, and his death-denotative name.

Likewise, this crucial flashback scene is reminiscent of P.K. Dick's assertion that the Roman Empire never really ended, merely walked-through and shed various skins. Jim Morrison alludes to a similar conclusion in "The End," with his line, "Lost in a Roman wilderness of pain" -- a verse pointedly used in the soundtrack of Coppola's Apocalyse Now.

We then learn that the teenage Harmonica had an older brother, who in flashback stands on Harmonica's tiring shoulders in the desert heat. The brother has a noose about his neck that's suspended from a church-bell, which in turn hangs from the center of the arch. When Harmonica eventually exhausts and falls, he will be forced to cause his own brother's death by strangulation. Young Frank, having arranged the scene, observes with satisfaction while one of his stooges bites into an apple. "Keep your loving brother happy" taunts Frank, in the film's tagline.

It is brotherhood, the male bond -- not merely an individual adversary -- that Frank wishes to exterminate from Earth. That, and not any particular person, is the true threat. Therefore Frank freezes the Crucifixion in time, endlessly repeating it psycho-socially via the guilt of the aging Harmonica. Civilization can thus be terrorized, zombified, The Empire extended indefinitely. Like the doings at Mesa Verde or Nuremberg, it's mass control, sorcery on a grand and ancient scale.

Harmonica doesn't dispatch Frank merely for personal vengance, but as a necessary step in the preparation, and cleansing, of the Land before a new age can begin. The two square off, tangential to the sun, like teams switching baskets at halftime, to ensure that neither is disadvantaged -- that, as Nature, Fate, and/or God intends, the ancestors are satisfied, and the best man triumphs and kickstarts the Golden Age.

Cheyenne, simultaneously, complements Harmonica's death-dealing by helping establish Jill as the "font of Life" for the coming civilization. Knowing that he will soon die, Cheyenne abruptly pats Jill's butt, and at her startled and offended response, sagely advises: "Make believe it's nothing." Wisely, as with Harmonica's earlier trashing of her lace bodice, Cheyenne is desensitizing her to match her new environment and responsibilities: she must not over-react (and over-legislate) in response to the rough men whose broken backs are building her new civilization.

Clearly, in the hysteria and power-seeking of 20th Century feminism, Cheyenne's advice has gone unheeded. Even more crucially, Harmonica's work is not yet done: Leone's film isn't truly retrospective, but premonitory. The Empire still grinds on, the Beast's hand rattles over the land and the people. Small men and women, with small motivations, occupy high places, even more than in the late Nineteenth Century American West. Now they own restaruants, preach patriotism, and build cages for human beings at a tidy profit. They're our leaders . . . guppy demagogues and cowards, not big enough to be truly evil in the grand style of Leone's Frank, not brave enough to face down Harmonica or The Kid in a fair fight.

Like the Deputy, they call for Ten Steps, but wheel around at eight, hoping to ambush men like Leone and Peckinpah -- both very flawed and often intemperate guys, to be sure -- from behind a rock . . . or a desk.

Peckinpah's Pat Garrett was eviscerated for three decades by such little people with big egos, mouths, and pocketbooks. Sorry Hollywood types that vampirize the blood of genius.

Only after Sam's death did the cocoon of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid finally open.

But, as Harmonica no doubt would have predicted, eventually it DID open, and if, in the end, is more important than when. We not only have Leone's languid masterwork available, but Peckinpah's as well, reminders that great men once existed, and can exist again, anytime one is willing to pay the price.

I have been with the best that the bastards could muster

From Danny the Dildo to Sidney the Snake

And I feel like a working girl pausing to wonder

Just how much screwin' the spirit can take

I said Willie old buddy, please tell me again

The reason to keep goin' on

Said there's no harder words to say over a friend

They done you so righteously wrong

They stopped you from singing your song

He was our hero, boys, he took the bullet

But he went down swingin' his fists from the floor

You can ask any working girl south of the border

Sam Peckinpah era un hombre for sure

"Sam's Song" (Kristofferson)